Last week community leaders in Eckington made the case for restoring the Comprehensive Plan’s Future Land Use Map Amendments that would allow housing on the industrial land near the metros and along the trail in their neighborhood.

As they laid out, these amendments would seem to be a home run. In addition to its transit accessibility, the large area in question could accommodate a significant chunk of the city’s housing goals (including two large District-owned lots that are primed for affordable and deeply affordable housing). And unlike other neighborhoods that have organized against similar map amendments, these were supported by the neighbors and ANC alike.

Proposed FLUM Amendments 2419.2 and 2419.3 would add residential and commercial uses designation to the industrial land in Eckington.

But according to DC Council Chair Phil Mendelson, whose decision to remove these amendments from his draft version of the plan has sparked lots of conversation and debate, the issue is not anything about these specific parcels, but rather a concern with our city’s limited supply of Production, Distribution and Repair (PDR) land overall.

As he expressed to the Washington Business Journal, his concern is a classic collective action problem:

“No one wants a concrete plant or an auto repair shop near their house, but we need them…Are we all going to have to go out to the suburbs to get our cars fixed? At some point, we’re going to wake up and say, ‘Geez, there’s no land left for the warehouse or the concrete plant.’”

Mendelson’s comments suggest we’re facing a dramatic supply squeeze for unpopular but essential facilities in DC. If we shrink the limited industrial land available, he worries, we’ll ultimately leave these necessary businesses with nowhere else to go in the city.

It’s not an irrational concern, but it doesn’t appear to hold up to closer scrutiny.

When the city completed the Ward 5 Works study analyzing industrial land in the city in 2014, they found that a large percentage of PDR land was being used for non-PDR uses. In the map below, numerous retail, civic and even residential lots are sited in the relevant areas.

Map of current uses of PDR-designated land in the 2014 Ward 5 Works study

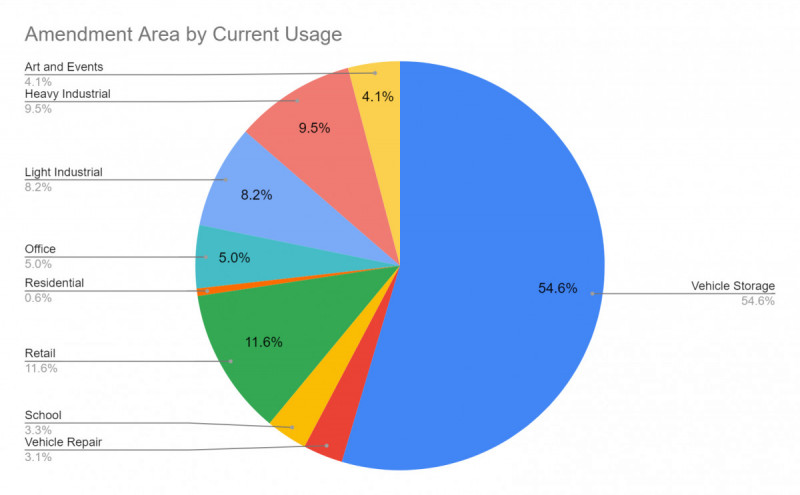

To assess the Eckington area in question more closely, and see if anything has changed since 2014, I’ve put together a similar analysis of current uses. The main takeaway is the same: these parcels are hardly being maximized for PDR-only uses. In fact, the vast majority of the land appears to be used for facilities that could equally locate themselves in commercially-designated areas, be easily combined with housing, or are simply providing storage for vehicles that would face little cost relocating.

Distribution of land in the FLUM amendment area categorized by present-day land use.

Non-PDR required uses - 27%

The topline takeaway is that a full quarter of the land (300,000 sq ft) is being used for facilities that have no requirement to be in PDR lots anyway, and have far more land across the city available to them if they chose to move in the future. This includes retail (a UHaul moving and storage facility), office space (a DC Library administrative building), some art studios and event spaces, and a school.

The north face of the DC Library Lemuel Penn building. The new mixed-use ONE501 building can be seen in the background. Image by the author.

The only edge case in this category is the Chair’s primary example of auto-repair shops, of which there are three here. Setting aside Mendelson’s contention that driving to the suburbs for car repairs is unthinkable (I would hazard a guess that tens of thousands of District residents who service their cars at large suburban dealerships find this entirely normal), auto repair shops don’t appear to be limited to PDR-zones. A cursory search reveals dozens of shops scattered throughout the city in regular commercial zones. If there’s a land crunch for these businesses, it’s not uniquely a PDR problem.

Mt. Pleasant Auto Repair Shop which is located in an area designated commercial on the FLUM

Light industrial - 8.2%

Another ~90,000 sq ft is currently being used for genuine production, but not in a way that would preclude sharing space with residential or commercial. The most prominent example is the ghost kitchen under construction on 5th St NE. Such facilities are easily compatible with housing, and can even be major assets. For a great example, you only have to look half a mile down the trail at the Eckington Yards project where Union Kitchen is acting as an anchor tenant in the mixed-use project’s commercial first floor.

The remaining 65% is split into two distinct categories:

Vehicle storage - 54.6%

The majority of the space is currently being used as vehicle storage for three entities. USPS has an apparently empty warehouse plus a parking lot hosting some postal vans. DC’s Office of the State Superintendent of Education stores their fleet of special education buses in another. And then Fort Myer uses a single, massive 450,000 sq ft lot running along the train tracks predominantly to store their fleet of dump trucks and some other construction vehicles.

The USPS warehouse with “For Lease Industrial Space” sign. The postal vehicle parking lot is on the North side of the lot. Image by the author.

In all three cases, it’s not clear that having vehicles occupying prime Metro-accessible land is an efficient allocation of space given that their primary purpose is to connect people and resources in completely different locations anyway. These vehicles would almost certainly be of equivalent or near equivalent value to their owners in slightly further away locations (even outside of the District). And the relocation costs would be small. All told, the District should not be losing too much sleep if these users decide to relocate their fleets to cheaper land elsewhere.

Heavy industrial - 9.5%

Finally, we get to the concrete plant Chair Mendelson evoked in his example (though in this case it’s technically an asphalt plant operated by Fort Myer).

Fort Myer’s asphalt plant.

Arguably, a similar case about relocation can be made for these heavy industrial uses. Unlike commercial and residential buildings, whose value is directly proportional to how close and connected they are to the full network effect of the city, industrial uses are far more specialty and situational, often involving vehicle transport anyway. A warehouse in a more rural area means slightly longer trips for its deliveries (maybe). A restaurant in a rural area means a radically shrunk (if impossibly low) number of customers. Housing in a rural area means significantly less access to jobs, amenities and city resources.

The argument for housing these kinds of heavy industrial facilities inside the city anyway is that they generate economic activity and jobs that benefit the city as a whole (though this benefit should be weighed against the damage they do to immediately adjacent communities). But there are other job-creating industries that are also essential to city life that we aren’t in a rush to find space for. We’re perfectly comfortable “importing” most food from outside the city because it’s far more efficient for the producers and customers alike. Is there any reason asphalt couldn’t be the same?

Furthermore, it’s not entirely clear the jobs equation is an up-or-down binary. The District’s job market is part of a larger regional whole. Only about 30% of DC’s workers actually live in DC, the rest are commuting in from outside jurisdictions already. Is an industrial facility within DC likelier to employ District residents? Maybe slightly? Would the commercial-like light-industrial business that would possibly replace it under a residential/industrial designation provide a similar number of jobs? Probably.

But even if we discount those arguments, and accept that there is a unique value to having heavy industrial facilities within the city, we’re still only talking about <10% of this entire area.

Again, based on the Ward 5 Works study, that’s not unique to this section. The image below shows another version of the earlier map, this time isolating the non-governmental/non-transit PDR-use lots. Far from the supply-crunch scenario the Chair is concerned about, the reality looks a lot different, with “true” PDR requiring far less land than is currently designated.

Map of non-governmental, non-transit PDR-uses from the 2014 Ward 5 Works study.

Given these ratios, the risk of allowing some mixed-use housing/industrial onto a metro-and-trail-accessible portion of this land looks a lot lower, particularly compared to the obvious benefits. The Council should restore the Office of Planning’s amendments to do so with confidence at its next markup of the Comprehensive Plan.